Book review on The 1619 Project

Review by Brian D. Roesch. The 1619 Project, on racism in US, is presented here, after last week’s newsletter linking US racism in US and in Viet Nam War Origin.

Free weekly newsletter: Real Reason for the US-Viet Nam War. Each Saturday, by 7a.m. East Coast US time.

Book Review by Brian D. Roesch, 12 February, 2022

Hannah-Jones, N., Roper, Caitlin, Silverman, Ilena, Silverstein, Jake, & New York Times Company. (2021). The 1619 Project : A new origin story (First ed.). New York: One World.

In this review, where page references are cited alone, they are to this book.

This 624-page book published in 2021 expands on the shorter, 2019 publication of 1619 Project by The New York Times. A Pulitzer Prize went to the introductory essay in that 2019 work.

This 2021 book establishes core facts, with details, and it provides cites to original sources. Notably, critics generally are not challenging these core facts. “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts,” a 2019 article in The Atlantic is titled. Indeed, the core facts are solidly proven and stand unrebutted. Critics, instead, object to some conclusions.

Tying the core facts together, the book’s main thesis appears to be that the cruelty used during the pre-1776 era carried forward, during centuries of inexcusable events against human beings, producing a cruelty today, with which some whites say the wealth gap is just tough, that’s the way it is.

While that may offend some whites, that thesis does tie US history together: The book calls today’s wealth gap a "stark reality" that started with brutal slavery for profit and continues into today (pp. 455– 58). The book’s writers are experts (qualifications pp. 551–53), including 12 eminent professors and 6 top-caliber journalists. The thesis is based on irrebuttable core facts.

Without rebutting the facts, many critics say that 1776, with its ideal of freedom, is the real start of US history, and that we have always been on a march toward equality. But that logic means we can’t expect too much equality from America after only 502 years. After all, that logic infers, this is about Black people, so 502 years without equality is nothing to get too concerned about.

In a nice feature for readability, one-word topic titles of the 18 chapters invite readers of varied interests, while each chapter’s contents interconnect with overall core facts and principles. A chapter titled Traffic shows that much congestion stems from interstate highway construction erected as barriers between segregated areas. In Justice, we learn that Homestead Act land giveaways during 1868–1934 went to whites only, while 4 million Blacks freed from slavery in 1865 were intentionally kept landless and hungry, to thwart a biracial society. Harmony sounds in the Music chapter, which says “music has midwifed the only true integration this country has known. . . something thrillingly crucial . . . the sound is staked upon: humanity.”

These 18 chapters weave the core facts to overcome unsupported assertions about false progress, a concern underlying a quoting of W.E.B. Du Bois in The Atlantic in 2019: “much of American history has been written by scholars offering ideological claims in place of rigorous historical analysis.” [i]

Core facts:

(1) During 1619 to 1776, 157 years of enslavement occurred, with 50 efforts to revolt, and the founding fathers knew it was brutal. Those 157 years were as long as the period from the Civil War to today, 1865–2022, 157 years. That was a long time for Black people to endure brutal enslavement, and for white people to dish it out. On the brutal side, Black people were considered chattel property, by law. So, the 1664 General Assembly of Maryland decreed that all Negroes shall serve durante vita, hard labor “for life.” (p. 278). The 50 attempts to rebel (p. 103) reflect the horror in the Blacks and the knowledge in the whites. Indeed, from 1704 onward, whites created patrols to quell unrest. (p. 104). Rebellions were brutally crushed, as in 1712 in New York: “Twenty-one people were executed: some were burned at the stake, while others were hanged in chains or had their necks snapped. One rebel was strapped to a large stone wheel, each of his bones broken with a wooden mallet while he screamed in agony, and then he was left to die painfully.” (p. 103). One-fifth of the US population was enslaved by 1776 (p. 427).

Thus, enslavement was a major fact of life. Whites knew their brutality was on a large-scale. Indeed, in 1774 Thomas Jefferson wrote that, “The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire . . .” But in 1776, he was persuaded to omit that from the Declaration of Independence. (pp. 426–27). By participating in the brutal 157 years, he and other drafters were hypocrites.

Some critics object to Blacks claiming to be at the center of US history starting in 1619, rather than all Americans being at a center that starts in 1776 with the ideal of freedom. But the core facts are undenied. Indeed, that 157 years shows that Blacks have struggled much longer than whites to achieve the US freedom ideal, particularly because some whites were the enslavers against freedom. And as shown below (in sections 3 and 4), after the Civil War the federal government acted to defeat the ideals of 1776 by allowing Southern murders and domination. And a later, October 1, 1926 Bristol Western Press (England) editorial cites: “the dementia of a mob that still tears a Negro to pieces or burns him alive for his alleged crimes . . . the difference between theory and practice of democracy in the United States.”[ii]

Some critics say The 1619 Project errs in claiming that the American Revolution was to defend slavery. They say the fighting started in northern colonies where anti-slavery was important. But the revolution also relied on southern colonies that practiced enslavement. There, enslavers angered at the Somerset decision (1772) freeing slaves in England, and the Dunmore Proclamation (1775) freeing slaves in American colonies. The angry Southerners included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. They joined the revolution, partly to defend slavery. (p. 15). Saying that anti-slavery Northerners started the revolution is like saying a football team only has an offense. Once the Northern colonies scored at Concord, the British charged back against the team’s defense that included General Washington.

The chapter titled Politics shows that during 1816-1860, free Blacks spoke, wrote, and petitioned to Congress and the Supreme Court for the US to follow the Declaration of Independence. (pp. 226–230). In 1830, the Legal Rights Association wrote that the Declaration of Independence meant the birthright was “all men” are “born free,” have “certain rights,” emphatically termed “inalienable.” (pp. 233–34).

In Chapter One, Democracy, Pulitzer Prize-winner Nicole Hannah-Jones writes that her father, like so many, proudly flew the US flag and served in the US armed forces, despite being subjected to severe segregation and low pay.

(2) The 1794 introduction of the cotton gin made brutal enslavement workdays longer than sunup to sundown, and caused the South to extend slavery into much more area. In factories, the cotton gin processed as much cotton as enslavers grew. This meant the enslaved worked longer hours, from before sunup to sundown, and longer on moonlit nights. Lunch breaks were 15 minutes long.

To produce even more, the US seized millions of acres, often by military force, from Natives, in Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, as well as Tennessee, Kentucky and more. The cotton expansion covered 800,000 square miles, and to work it, many of the enslaved were sold and brutally marched into the interior, at a cost of tearful tearing apart of families. Some credit financing was provided by New York financial institutions. Details are shown in the The 1619 Project, in Slavery’s Capitalism, (pp. 19, 32–37), and in Edward E. Baptist’s The Half has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (2014). (Kindle locations 377–407 and 621–754). These facts are not contested by critics.

To produce yet even more, enslaver accounting records showed quotas for each slave and daily picking totals, so that at the end of each day, those who failed to meet quotas were whipped. (pp. 177–80). The book says that was part of the development of the capitalist business model. Without contesting the fact, critics contest that conclusion by saying that capitalism developed just fine without slavery. The book’s answer is that slavery did occur and that accounting method was used.

(3) In 1865, 4 million Blacks were freed from slavery, but no land was given or sold to them even though, during 1868–1934, the government gave free land to 1.5 million whites under the Homestead Act. In 1865, the Civil War freed 4 million Black people. They had no land and no work. The federal government allowed the defeated white Southerners to keep their lands, while no land was given, or even sold, to the 4 million Blacks.

At virtually the same time, the Homestead Act provided free 160-acre tracts of land. During 1868–1934, the federal government gave such lands to whites, but excluded Blacks. The giveaways included enticing white foreigners to immigrate for free land. More than 1.5 million white families received free land. The lands allowed whites to build wealth, but Blacks remained in landless poverty. Today, about 20 percent of white adults are descended from those homesteaders. (pp. 458–62).

The United States Government had the power to confiscate the lands of those who had fought to destroy the US, the power to imprison those rebels, and the power to distribute their land to the freed slaves. General Sherman even started redistributing land. But President Andrew Johnson (1865–69) and some members of Congress falsely said that assisting the slaves would only breed dependence—in fact, Black leaders offered to pay for the land over time. But Johnson granted amnesty to the rebel leaders and, rather than prison, he let them hold southern government offices and set up a system close to slavery (see next section). In 1866, he stated, “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men.” He canceled General Sherman’s land redistribution. (pp. 259, 297, 390, 459–61).

That action and statement show that the federal government intended to destroy the Black people’s ability to have any economic equality, intended to destroy the prospects for a biracial society, and intended to destroy the 1776 ideal of freedom as far as it related to Black US citizens. While Congress battled him and bestowed citizenship on Black people in 1866 and 1868 (see below), enough pro-slavery sentiment existed that he had the power to take those actions by the US Government.

From 1865 onward, The 1619 Project (p. 389) describes:

Freed people did not have enough food, clothing, shelter, or medical care. They were plagued by dysentery, cholera, and a bleak roster of other diseases . . . As a result, the death toll of Black people surpassed that of white people by an overwhelming and consistent margin. As the historian Jim Downs details in his 2012 book Sick from Freedom, the newly emancipated died in such high numbers that in some communities their bodies littered the streets.

Downs points out that “The onset of famine in 1867 led to chilling mortality rates among newly freed slaves.” Famine lasted into 1868.[iii]

The famine was compounded by white Southerners murdering many Blacks (see next section.)

After the Homestead Act giveaways ended, Blacks were cut out of the next set of federal assistance:

98 percent of the loans the Federal Housing Administration insured from 1934 to 1962 went to white Americans, locking nearly all Black Americans out of the government program credited with building the modern (white) middle class.

“At the very moment when a wide array of public policies was providing most white Americans with valuable tools to advance their social welfare—insure their old age, get good jobs, acquire economic security, build assets, and gain middle-class status—most black Americans were left behind or left out,” the historian Ira Katznelson writes in his book When Affirmative Action Was White. “The federal government . . . functioned as a commanding instrument of white privilege.” (p. 466).

(4) During 1866–1950s white Southerners held political control of the South (along with some federal activity into 1877 in the period called Reconstruction), passed laws dominating Blacks, and murdered at least 6,500 Black US citizens, condoned by federal government despite the Civil War outcome.

The US victory in the Civil War opened the door for a biracial society and equality meeting the ideals of 1776, but the US government acted quickly to deny the 1776 ideals: It allowed Southern states to pass laws against equality, and it allowed Southerners to murder and massacre Black people in order to keep them in lower paying jobs, out of political office, and not living in white residential areas. Southern laws called Black Codes made it a crime, for example, if Blacks didn’t sign labor contracts with white landowners, changed employers without permission, or sold cotton after sunset. Often, Blacks had to work for their former enslavers. (pp. 113, 280–82, 433, 465)

Though Blacks were included as citizens in the 1866 Civil Rights Act and 1868 14th Amendment (pp. 233–34), and an Enforcement Act criminalized white domestic terrorism, the Ku Klux Klan and other vigilante groups were undeterred as they spread terror. The bloodshed was so intense that in the mid-1870s President Ulysses S. Grant acknowledged that white people had “the right to Kill negroes . . . without fear of punishment, and without loss of caste or reputation.” (p. 261)

That meant the US government supported the fight against the ideals of 1776. (See also prior section.)

Southern vagrancy laws meant Blacks could be arrested for standing on a street corner, then thrown into a convict leasing system in which they were forced to pick cotton or do other work. Whites who leased Blacks in this system had little incentive to keep the “criminals” alive. Some places had almost a 45 percent death rate. (pp. 113, 279)

Some critics claim that this book errs in saying that race was the reason that white murdered Blacks; they say, instead, that it was due to a class conflict of the wealthy against the poor. While class may have been a factor, it was not the main one, because (a) from 1619 onwards, whites regularly murdered Black slaves but not poor white workers, (b) some poor whites in the South took part in the 6,500 murders of Blacks, (c) some unions with poor white workers excluded poor Blacks, and (d) the viciousness of many of the murders had a distinctly racial character. In Pine Bluff, Arkansas, during Johnson’s presidency (1865–69), whites rounded up Blacks in one area and burned their homes. The next morning, a visitor to the area saw 24 Black men, women, and children dead, hanging from trees. Former Union General Carl Schurz traveled through the South and documented the results of many horrific killings. He wrote that Blacks leaving the plantations “were exposed to the savagest treatment.” Hunting parties chased down Blacks, shot them, and let dogs devour their faces. (pp. 182–83, 260).

“Any stride toward freedom by Black people provoked alarm throughout the South, as any perceived increase in Black political and economic power triggered white fears of losing power and status.” (p. 112). Whites acted to prevent violations of white social codes, lack of deference to whites, consensual interracial sex, requests for higher wages, and economic success. (p. 299).

The book reports, “the orgy of violence known as the Red Summer, which began ramping up as World War I was winding down. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and others, identified ‘at least 25 major riots and mob actions . . . and at least 52 black people . . . lynched. Many victims were burned to death’ between April and November 1919.” (p. 261).

In 1947, the Truman Administration issued To Secure These Rights: The Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, which, in the Chapter titled Progress, Boston Univ. Professor Ibram X. Kendi calls “one of the most powerful indictments of racism ever to come from the U.S. government.” And in 1951, the Civil Rights Congress delivered a petition titled We Charge Genocide to the United Nations, detailing that 1945–51 had 152 murders and 344 other crimes of genocide against Blacks. (p. 434).

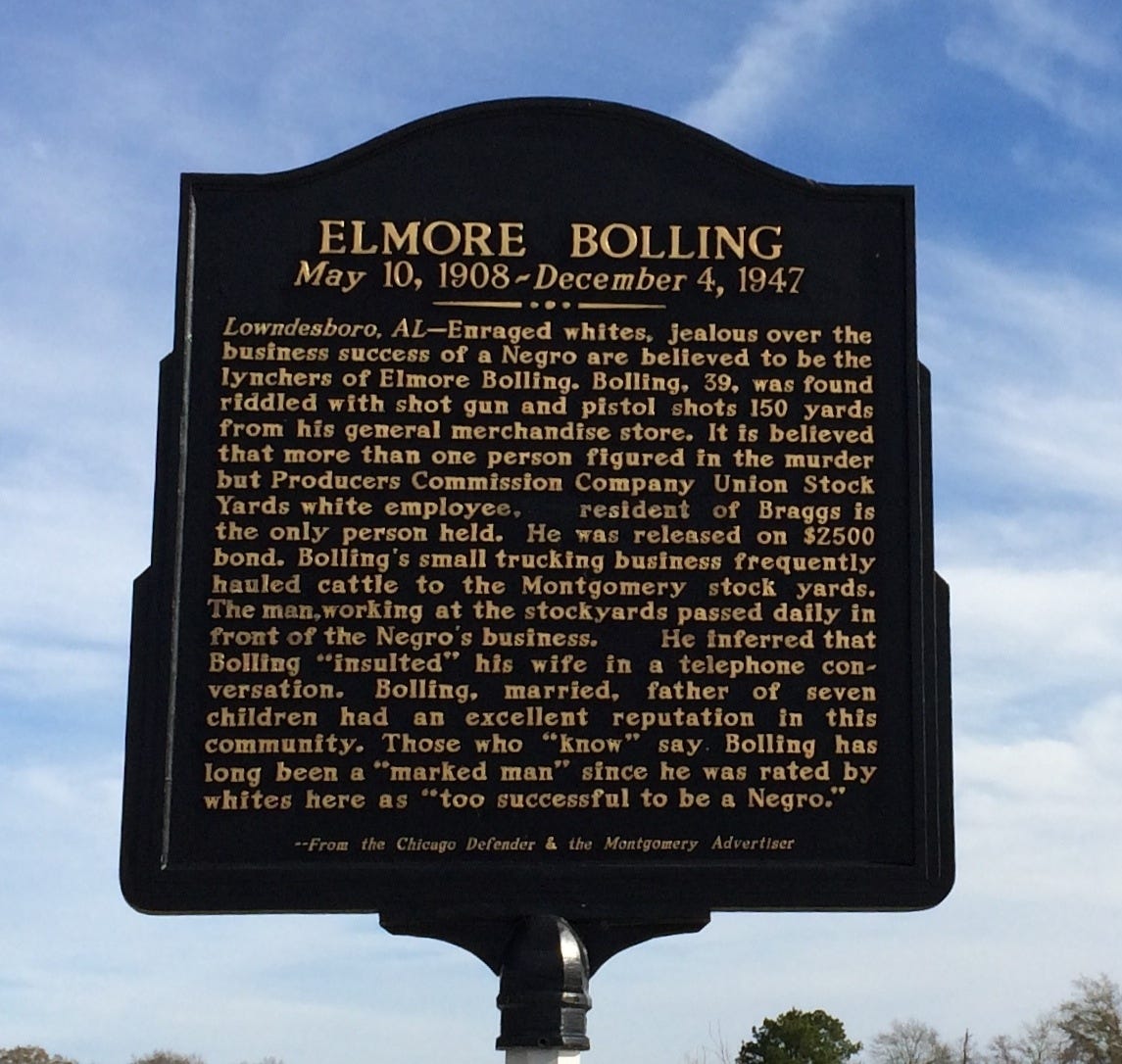

Bridging the post-civil War and post-World War II eras, in Alabama during the late 1880s, the grandfather and father of Elmore Bolling acquired land and cattle. A white man rented from them, then convinced a court that the land was the white man’s. Blacks having few rights in court, Elmore’s grandfather and father lost the land. From that, grandson Elmore Bolling decided only to rent land. By the mid-1940s, he and his wife, Bertha Mae, had built a successful general merchandise store in Alabama, developed a delivery business, and gained customers by selling Sunday dinners to the after church crowd, and selling ice cream they hand cranked. After a white service station refused to sell to him, he added a gas pump. That was too much. One day in December 1947, a deputy sheriff and another man came to the store asking where he was. Then in broad daylight outside the store, that other man and a second man, both unmasked and white, waited for him. When he returned and stepped from his truck, they confronted him, then shot him seven times, one a shotgun blast. His wife and three young children rushed out to find him dead. (pp. 292–96).

Elmore Bolling Historical Marker, Lowndesboro, Alabama. Historical Marker Database. Photographer Mark Hilton, 2013.

(5) During the 1950s until today, successive waves of white backlash generated by attitudes fueled from 1619 onward have undercut Black citizen equality.

Another white backlash against Blacks stepping out of line came after many whites angered at the May 7, 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, that school segregation was unconstitutional. White Citizens Councils formed in 1954 throughout the South, using economic pressure and the threat of violence to maintain segregation. In mid-August 1955, Black cotton farmer Lamar Smith went to the Brookhaven, Mississippi courthouse to pick up absentee ballots for Black citizens so they could more safely vote. While dozens of people watched, including the sheriff, Mr. Smith was beaten severely, then shot in the heart and mouth. He died. On August 28, 1955, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black US citizen was tortured, mutilated, and murdered by whites.[iv]

In Chapter 17, Professor Kendi argues that saying that the nation has progressed racially is “used all too often to obscure the opposite reality of racist progress.” He points out that the early history (in the core facts) shows that racist attitudes were widespread, so they are the real US.

After murders continued in the 1950s, the federal government decided that a “Second Reconstruction” was needed because the first had failed. The government passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act. A white backlash started in the 1960s and lasts into today. During 1967 and 1968, inner city ghettoes exploded in riots, due to frustration over a severe wealth gap, lack of opportunities, and attitudes of many whites. But rather than face the racial inequities, and the causes dating from 1619, the Republican Party played to the racist white backlash.

(6) From the 1960s into today, the Republican Party’s courting of voters in the white backlash against civil rights laws has fueled white attitudes of avoiding the centuries of causation of inequities. This undercuts the national effort that the 1968 Kerner Commission said was needed to overcome the inequities. It has led to unwarranted white attitudes causing the death of some blacks and the mass incarceration of some others.

As the book says, “By the 1960s it was less acceptable to employ the same forms of extralegal racial terrorism that had been used to constrain previous forms of Black protest. The national government, rather than leading towards economic equality for Blacks, pursued a new politics of fear and anger that led instead of economic development, to the current era of mass incarceration.” (p. 281). In such politics, other books detail the Republican Party strategy of courting voters in the white backlash.[v]

On today’s aftermath from the past, the book says, “. . . it is Black and other nonwhite people who are disproportionately targeted, stopped, suspected, arrested, incarcerated, and shot by the police or prosecuted in courts. Hundreds of years after the arrival of the first enslaved Africans, a presumption of danger and criminality still follows Black people everywhere.” That describes the recent murder of Ahmaud Arbrey who was jogging, and three white people assumed that he must be a dangerous criminal. This case, including three murder convictions and life sentences for the whites, illustrates the book’s point that after centuries of considering Black people as lesser beings, part of US culture has that in its DNA. (p. 281).

A white’s wrongful assumption is also identified in the 2020 death of Dr Susan Moore, MD, from Covid-19. She says on video that she was not given a diagnostic examination even though she explained to the attending physician that she had extreme neck pain. A later CAT Scan showed that Covid-19 was spreading in her. Within weeks, she was dead.[vi]

The book says this is a critical moment in US history. We will either “double down on romanticizing a false narrative” or we will realize “that there is something better waiting for us, if we can learn to deal honestly with our history.” (p. 282).

That observation in the book points to a simple principle that the US claims to follow: Take responsibility for your actions and strive to correct your errors. People will then respect you. We teach that to children. “A society recovering from a history of horrific human rights violations must make a commitment to truth and justice. As long as we deny the legacy of slavery and avoid this commitment, we will fail to overcome the racially biased, punitive systems of control that have become serious barriers to freedom in this country. It’s tempting for some to believe otherwise, but much work remains.” (p. 283).

(7) A 10 to 1 wealth ratio exists today (12 to 1 says Color of Money).

The final chapter points out that “it is white Americans’ centuries-long economic head start that most effectively maintains racial caste today.” (p. 456). A 10 to 1 racial wealth gap exists. (p. 470) Another book, Color of Money, p. 249, says it is 12 to one. Worse, white families with children have a 100 to 1 wealth advantage over for Black families with children, says a 2020 report from Duke and Northwestern universities. (p. 457).

Wealth gap effect on children. For the first 20 years of life, children of the average white family have many more advantageous experiences and opportunities than children of the average Black family. “Wealth . . . is what enables you to buy a home in a safer neighborhood with better amenities and better-funded schools . . . send your children to college without saddling them with tens of thousands of dollars of debt . . . money for a down payment on a house . . . prevents family emergencies or unexpected job losses from turning into catastrophes . . . ensures what every parent wants: that your children will have fewer struggles than you did.”

But many critics fail to even mention children in relation to the wealth gap.

It has led to inheritances in white families being much larger than in Black families. Receiving an inheritance boosts white families’ median wealth by $104,000, but for Black families it is only just $4,000. (p. 300).

The existence of the wealth gap caused by racist practices supports what Kendi says in Chapter 17: “Saying that the nation has progressed racially is usually a statement of ideology, one that has been used all too often to obscure the opposite reality of racist progress. And it’s been this way since the beginning.” (p. 425).

Conclusion. By extensively developing core facts, which critics decline to attack because the facts are so well-researched and supported by original sources, this book—along with many others based on deep scholarship—paves a realistic pathway to end the “stark reality” of the wealth gap and the damaging influence of attitudes that maintain it. A preliminary view of a resulting biracial (multiracial) society appears in numerous photos in the book. They show people whom many whites would discover are marvelous neighbors.

To get past the grotesque 10 to 1 wealth gap would require a modest continued growth in the large movement that has grown in the period between the murder of George Floyd and the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, and criminal convictions in both murders. When the movement has sufficiently grown, voters could require Congress to authorize compensation.

Another important part of the pathway is the education of all schoolchildren about the unfair origins of the 10 to 1 wealth gap. Children would learn about slavery, in age-appropriate curriculum. They would learn of unfairness in the Homestead Act land gifts for 66 years to whites, while excluding Blacks who, freed from slavery, had nothing. They would learn that the 1968 Kerner Commission found “that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” Ghettoes had poverty, inferior schools, few jobs, lacked opportunities for youth, and allowed little or no ownership of capital-generating property. Kerner Commission Report, pp. xiii, 1

The schoolchildren’s growth into adulthood, armed with facts, would allow them to have knowledgeable discussions about race. This has been denied to older generations lacking the true facts finally assembled in this book

This pathway would directly deal with what the book describes as: “This remarkable imperviousness to facts when it comes to white advantage and architected Black disadvantage.” (p. 468). The imperviousness to facts is serious. It brings up an elemental metaphor of “DNA,” for which the book cites Yale Univ. Professor David Brion Davis. Davis wrote in 2006 that, “racial exploitation and racial conflict have been part of the DNA of American culture.” (p. 29). And, the book cites a 2016 expansion of the DNA metaphor by Harvard Univ. Professor Sven Beckert and Brown Univ. Assoc. Professor Seth Rockman: “By virtue of our nation’s history, American slavery is necessarily imprinted on the DNA of American capitalism.” (p. 167) In their book, Slavery's capitalism, pp. 15, 31 52, Professor Edward E. Baptist supports that metaphor, pointing out that the cotton gin’s faster processing led to “torture” of slaves—he gleans details from source accounts—that caused them to increase their production 400 percent between 1810 and the 1850s. To “torture” black-skinned humans to increase profits, a cruelty as elemental as DNA was imprinted in our US capitalism and in our culture.

So, by presenting the facts with which to show schoolchildren the truth, this book makes a meaningful contribution to our society, The 1619 Project's 12 professors and 6 journalists stand as a major force in presenting this accomplishment. By reading this remarkable book, people can see the right thing to do on the wealth gap, an “architected” violation of America’s stated, great ideals.

[1] Du Bois quote. Serwer, Adam (23 December, 2019). “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/12/historians-clash-1619-project/604093/.

[ii] Bristol editorial. Ginzburg, R. (1962). 100 years of lynchings. Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, Kindle location 2621.

[iii] Famines. Downs, J. (2012). Sick from Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 8, 40 44)

[iv] Emmett Till, Brown v. Board, mood of South, murders of vote workers. Tyson, T. (2017). The blood of Emmett Till. New York: Simon & Schuster, Simon & Schuster Digital Sales Inc., pp. 76–78, 84, 91–100, 110–112, 119, Kindle locations 1294–1323, 1441, 1551–1716, 1898–1936, 2065–2071. Emmett Till, see also this newsletter 5 Feb, 2022.

[iv] Maxwell, Angie and Shields, Todd (2019). The Long Southern Strategy : How Chasing White Voters in the South Changed American Politics. NY: Oxford University Press; Haney-López, I. (2014). Dog whistle politics : How coded racial appeals have reinvented racism and wrecked the middle class. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–4.

Other cited Bibliography

Baptist, E. (2014). The Half has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. NY: Basic Books, Perseus Book Group

Beckert, S., & Rockman, Seth. (2016). Slavery's capitalism : A new history of American economic development (Early American studies). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

[vi] Dr. Susan Moore #DemocracyNow Dec 30, 2020 “This is How Black People Get Killed”: Dr. Susan Moore Dies of Covid After Decrying Racist Care